Maynard Ferguson

Childhood

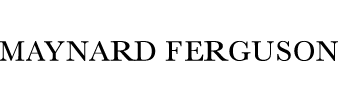

In 1928 a baby boy, Walter Maynard Ferguson, was born in the general hospital in Montreal, Canada. At age nine, after violin and piano lessons, he spotted a man playing cornet at a church social and said to his father, “Dad, get me one of those.” It was to be the beginning of one of the most successful careers in modern music history.

At age 11 he soloed as a child prodigy with the Canadian Broadcasting Company Orchestra and at 14 earned a scholarship to the French Conservatory of Music. Everyone who heard Maynard play – teachers, audiences and professional musicians alike – were in awe of his natural talent. From the very beginning he had an exciting and original voice in jazz that was unmistakably his own. Of course for young Maynard, it was all about having fun.

After his experience in the high school jazz band, which included his brother Percy and his schoolmate, the great pianist Oscar Peterson, he played with several local Montreal bands. At 13, he was invited by Louis Armstrong to sit in with his band, and at 14 he was playing 7 nights a week at a French Canadian nightclub in Montreal called the Palermo Café.

How Maynard remembers those childhood gigs.

MAYNARD

“When people got drunk and started throwing beer bottles, you got your head down. They’d be cursing and yelling in French. What an education! My mother and I would go home via a one hour ride on a streetcar. She was no longer teaching so she could take me to the gig and bring me home at two in the morning. I was very well protected.”

Maynard’s parents, both school teachers and his father a principal, knew that music would be Maynard’s profession, so they did everything to help him pursue his talents.

Around this time both Maynard and Oscar Peterson were getting a lot of attention from Canadian radio since television hadn’t arrived yet. And in 1945, when Maynard was just 17, Down Beat magazine described him as “A new star on the horizon.”

Luckily for jazz players, jitterbug was in and the music was pretty swinging. Maynard was leading his own jazz and dance band at age 16 and by 18 his band was the opening act for many of the great American bands traveling through Canada. Maynard received many offers to join American bands; one offer came from Stan Kenton.

Trombonist Milt Bernhart remembers that night.

MILT BERNHART

“None of us had ever heard of him (Maynard) before that night – including Stan. As we finished the set and began to leave the bandstand I glanced at the players taking our place and noted that they were younger than usual. I got as far as the door as they started to play – and I stopped cold. The first number started right off with this incredible stratosphere trumpet. It wasn’t coming from the trumpet section, but from the leader. And he kept building on it. We had Buddy Childers in our band with a good high range, but this range seemed to have no limit. And it wasn’t a thin squeezed sound – the kind that high note trumpet players almost always got. The sound was big and fat and very hard to walk away from. I didn’t walk away. I stood right where I was, and listened to the whole set. I don’t think I was alone standing there. Maynard knew he had caught our attention, and he unloaded everything he had – and he had a carload. He played trombone, and very well – he played a solo on baritone sax, also impressively. Everything was played with spirit and showmanship. I was completely sold. We all hung around, and for days it was the talk of the band. I knew that Stan had talked to him and made him an offer. But Maynard had commitments I believe that precluded his entry to the U.S.”

Coming to America – An Instant Success

By the beginning of 1947 the Swing Era was coming to an end. In this post-war period, several U.S. bands including the Benny Goodman Band, had disbanded due to the rising costs of transportation as well as well as different tastes in entertainment. Maynard felt that he had gone as far as he could with his Canadian band.

MAYNARD

“I finally decided I wanted to take up Stan Kenton’s permanent offer. I went to Immigration and discovered that they weren’t letting Canadian musicians into the United States. … At any rate, the immigration officials indicated that, to be admitted, I had to be a Symphonic Conductor or a musical genius. They asked, “Well, what qualifies you?” Without hesitation I replied, “I’m a musical genius!” It was great. They said “OK.” Then they could go on record as saying that they had been informed that I was a “musical genius,” so therefore it was OK. I mean it was just that easy.”

Maynard made it to the U.S. in 1948 at the age of 20, but right when Kenton took a year off. Since his immigration status only allowed Maynard to perform as a vaudeville act, he did a solo appearance at Café Society Downtown in New York City.

An attractive cigarette girl would shout out, “Here’s Tommy Dorsey,” and Maynard would take out his trombone and play “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You.” Then she would yell, “And here’s Artie Shaw,” and Maynard would play “Begin The Beguine” on clarinet. This continued through trumpet, saxophone, etc.

Word spread quickly that Maynard had made it to the States and Boyd Raeburn hired him as an “act.” It was one of the most progressive bands around with great players and great charts. Raeburn personnel had included: Dizzy Gillespie, Johnny Mandel, Roy Eldridge, Conte Candoli, Milt Bernhart, Shelly Manne and many other great talents. Maynard then did a stint with the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra. In 1949 he joined the Charlie Barnet Orchestra and received national recognition.

Charlie Barnet didn’t like the newly popular bebop style, but he set about forming a great modern big band. Maynard auditioned at Birdland, with his parents and “Bird” watching from the theater section. The trumpet section became Doc Severinsen, Johnny Howell, Rolf Erikson, Ray Wetzel and Maynard Ferguson.

DICK HAFER

“In March of 1949 I joined the Charlie Barnet Band. Shortly afterwards a lean dark-haired trumpet player from Montreal, Canada came on the band and proceeded to take high note trumpet playing to new heights. The precision of that trumpet section and the rest of the band I shall never forget. People who heard it in person are still talking about it.”

DOC SEVERINSEN

“I heard him (Maynard) warming up and I tell you, I wish every trumpet player who ever lived could have heard what he sounded like. I don’t know why I kept playing after that. Just the warm-up alone was absolutely frightening and then, of course, the gig came around and he did it all over again.”

Maynard’s featured number with the Charlie Barnet Orchestra was “All the Things You Are.” That piece alone brought him international acclaim among musicians and instant visibility with the listening society. The estate of the late composer, Jerome Kern considered the arrangement a “bastardization” and Capitol Records was forced to withdraw it from circulation, by order of the court. The record quickly became a collector’s item.

Joining Kenton

On January 1st, 1950 Maynard joined the Stan Kenton Innovations in Modern Music Orchestra. He played with the Kenton aggregation on and off for five years. Maynard always considered this band to be one of the most creative adventures ever in American music.

MILT BERNHART

“Maynard’s coming to the Kenton band was a “fait’ accompli.” After all, we heard him first! On tour with this large symphony-style orchestra, and featured on the wonderful showpiece that Shorty Rogers wrote for him, he was unquestionably the star of the evening – evening after evening. To say he broke it up every night is to put it mildly. Maynard Ferguson had arrived.”

DOWN BEAT MAGAZINE – March 10th, 1950

“Hollywood – Maynard Ferguson, ex-star of the ex-Charlie Barnet band, stood up at his end of the new Stan Kenton brass section and broke loose with some of the wildest, most unbelievable, most exciting (and, to some, most perplexing) trumpet playing ever heard anywhere. A young fellow sitting near this reporter grabbed the person sitting next to him (a complete stranger) and gasped: “The TOTAL end! The TOTAL end!”

Maynard took first place in Down Beat magazine’s best trumpeter poll for three successive years beginning in 1950. As a side note, his schoolmate, Oscar Peterson took first place for piano those same three years.

After his stint with Kenton, Ferguson spent three years as first-call studio trumpeter for Paramount Pictures in Hollywood. He recorded the soundtracks for many movies including Cecil B. De Mille’s spectacular The Ten Commandments. In 1955 he was the featured performer in the William Russo composition “Titans” with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic.

Maynard’s New Life in Hollywood

Excerpt from MF HORN

by Bill Lee

Maynard’s popularity in the Hollywood, Los Angeles area had grown beyond music circles and he began to have invitations to socials, which included people like Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Zsa Zsa Gabor, Peter Lawford, and others. Once, Lester Lannin, ultra-conservative society band leader in New York, called Maynard from New York to invite him to play for Gary Cooper’s birthday party. Mr. Lannin went on to say, “I’ve heard a lot about you jazz musicians and I hear how you guys are with women. I want you to come alone in a tuxedo and there’s a servant entrance in the back and I want you come in the back.” Maynard said, “Whatever you say Mr. Lannin.”

Maynard owned a XK150S, a very hot convertible Jaguar. Pianist Ian Bernard’s wife happened to come around that day with a friend of hers and they were beautiful. So he asked them to go with him. They dressed to the hilt and the three of them got in the two-seater Jag. He pulled up in the driveway of Gary Cooper’s house in his white convertible Jaguar, roaring the motor just to show off, and did a “Cary Grant,” leaping out of the car (without opening the door), and then opened the door for the ladies. As he walked in the first thing he heard was “Anything Goes” playing and people were dancing. He was, of course, much earlier than he was supposed to be, and everybody was there. Mrs. Cooper asked Sinatra to sing with the band and he refused! Maynard walked into the beautiful foyer and hadn’t met the Coopers yet, but the first guy who spotted him was Dean Martin and he was looking at the beautiful girls accompanying Maynard. Jerry Lewis came over in a shot and said, “Maynard!” Then Lewis hollered, “Hey Maynard, how’s your f**king chops?” It was so out of context with all the people standing around in their tuxes and gowns. Lester Lannin turned around, saw Maynard with his horn and two women, and was furious. He got off the bandstand and headed toward Maynard. Martin, Lewis, and Lawford also were heading towards Maynard at the same time. Just as Lewis got there he said, “Hey, Maynard are you going to blow some horn and get this party off the f**king ground?!” It was like f**king this and f**king that. Lannin was about five feet away looking like he was going to take care of this!

Then he heard Jerry and Dean and Peter were saying the same stuff and Lester said, “Ah, Mr. Ferguson, we’re glad you arrived what would you like to play first?” Like that, he was so slick. He just turned on a dime. Maynard sat in and there were a few really hip musicians on the band!

~ End Excerpt

Los Angeles in the 50’s

HERB GELLER

“I first started working with Maynard in Los Angeles. He was under contract at the time to Paramount film studios and was, at the same time, starting to get his own band together. At that time the instrumentation was three saxes, three brass, and three rhythm. Willie Maiden was playing baritone and writing most of the charts. He was a wonderful writer with an advanced harmonic sense and some of the arrangements were quite difficult. Maynard was always amazing with the things he could do. I’d never heard anyone with chops like that! He was also a wonderful person and an ideal band leader. He was always in a good mood and supportive of the musicians, encouraging us and with great patience always got 100% from everyone.”

MAYNARD

“We had a two week engagement with my big band which I had to put together with new music, an all-star group, sort of a dream band with Mel Lewis on drums. The show featured Carmen McRae and my big band. There were two jazz clubs on Vermont Street in Los Angeles, across the street from each other. The adjacent club featured Buddy Rich’s small band and Billie Holiday.”

During this time Maynard met Flo. She and her roommate Patty lived across the street and they were like a bunch of kids hanging out and having fun. They tried to stay friends, but one night listening to the Oscar Peterson Trio they fell in love. Flo became Maynard’s lifelong best friend, wife, counsel and confidant.

It had been a great six years. Hollywood, the fabulously beautiful West Coast, the movies, the Stan Kenton musical empire, the cream of the crop West Coast jazz players and writers, and Flo with all the happiness and adventure she brought Maynard. He had it all – but not what he yearned for. Maynard missed directing his own ensemble. He missed the jazz freedom he had relinquished for fame and money.

Little did he know he was going to be the leader of one of the principal components of the evolution of jazz in the second portion of the 20th Century.

The Birdland Dream Band

The decision to discard his availability as a side-man and dedicate his career to assuming the responsibility of organizing and directing his own group would prove to be a wise one. It was clear that personal financial gain was neither the motive nor the objective. Maynard set his sights on a new, exciting approach to big band jazz. The challenge included the retention and extension of the Parker-Gillespie-Monk melodic/harmonic approach propelled by the Basie-Herman rhythmic feel. The objective was clear. The implementation would depend on the charts and personnel.

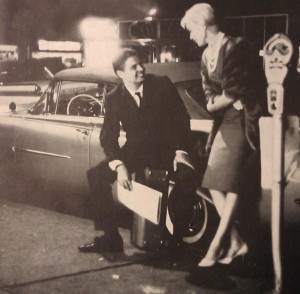

So in 1956 Maynard accepted an offer from Morris Levy to front the amazing Birdland Dream Band and moved his family to New York City. New York was the scene for jazz and Maynard crossed the country to be at the epicenter.

DOWN BEAT MAGAZINE – September 5th, 1956

FERGUSON TAKING ALL-STAR DREAM BAND INTO BIRDLAND

“Hollywood – Maynard Ferguson has left the West Coast to open at Birdland August 30th as leader of one of the most star-studded bands ever assembled.”

MAYNARD

“As part of my deal, I would end up with the book. So everybody that was hot in New York at the time was writing for the Birdland Dream Band. The idea was that I would rehearse for two weeks and perform for two weeks (which turned into four weeks). Then when we had tightened things up pretty good we would go into the studio. I didn’t feel like the real band leader, though, in the sense of it being “my band.” I was fronting an All-Star band for Birdland. That was very successful and everyone came to hear it. Some of the arrangers were Johnny Mandel, Bill Holman, Quincy Jones, Al Cohn, Manny Album, Ernie Wilkins, Bob Brookmeyer, and Willie Maiden.”

A typical evening at Birdland began with the Ferguson Band playing the Jimmy Giuffre composition, “Blue Birdland,” Maynard’s theme. The impresario, Pee Wee Marquette, would hug the microphone and announce, “Ladies and gentlemen, we have a real treat in store for you tonight here at Birdland, a man who plays a lot of trumpet. That’s right – the young man with the horn, the one and only, everybody put your hands together for Maynard Ferguson and his Birdland Dream Band. Maynard the Fox! Maynard the Fox!”

MAYNARD

“Miles (Davis) and I always got along so great together, and yet Miles would always be Miles. We spent a lot of time together, five shows a night each in Birdland, 14 weeks out of the year, six nights a week. That’s 30 shows and a lot of time in between, although there was like only five minutes between acts.”

Joe Glaser, Louis Armstrong’s manager, had heard the All-Star band at Birdland and told Maynard if he put a band together he would book it. And that was the beginning of Maynard’s first road band.

RICHARD HURWITZ

“One thing I’ve always been impressed about Maynard is his musicianship. I remember when the third trumpet player didn’t show up and Maynard played all the parts from memory. He just jumped in there and played the parts. The travel was always grueling and difficult and the locations were usually about 400 miles from each other. Sometimes we’d travel all night. It was basically a labor of love because there certainly wasn’t any money in it. We always wished he could afford to pay us a little more money, but of course he couldn’t. We always admired him. He was a great band leader.”

TONY INZALACO

“We played all the major festivals. I can remember some years working in New York for 18-20 weeks out of the year and that’s incredible. At one point, there were three clubs, Birdland, Basin Street East, Metropole, and, as far as I know, there was no exclusive contract with any place, so we got to work those three places and spend a lot of time in the city. We’d run into Duke’s band in Chicago or Basie’s band in Philadelphia. …Playing the World’s Fair in 1964 I can remember walking to the venue where we were performing and I saw two figures about 200 yards away in the midst of the crowd. One of them was Charlie Mingus, with a ten gallon cowboy hat and cowboy boots and Maynard looking like Jack Armstrong, the all-American boy. These two people, just hanging out together, was like one of the most unlikely sights.”

Family Life – Millbrook

During the early 60’s Maynard and Flo became close friends with Harvard professor and research psychologist, Timothy Leary. Leary was researching mind expansion and self-enlightenment through the use of psychedelic drugs. Flo had participated in his experiments at Harvard. So, when Leary and colleagues Richard Alpert and Ralph Metzner launched a community for psychedelic drug research on a magnificent estate in Millbrook, NY, Maynard moved his family into the main house. It was a nice drive to the city for gigs, and with its elegant lawns, stables and fruit orchards, the estate was a fantasy playground for his five young children.

Millbrook was ground zero for the psychedelic movement in America; the mansion hosted some of the most controversial and visionary personalities of the 1960’s. Leary described the communal experiment to be “free of social convention, where the human capacity for revelation, wonder and mysticism could be nurtured and explored.” For Maynard and Flo, it was a spiritual awakening in a utopian environment.

MAYNARD

“The Millbrook experience turned me on to a wider way of thinking. Before that my life had been music and family. It opened my thinking about many things – spiritual and musical. It was the beginning of my reading and listening to world philosophy and world music.”

But as news of events at Millbrook spread beyond the exclusive world of academia, curiosity-seekers began to turn up, and life on the estate took on an increasingly less spiritual quality. Maynard moved his family to the gatehouse of the property but the environment was changing and in the fall of 1966 the first of many police raids occurred. It was time for a new experience. Not only Millbrook had changed, but also the music world had changed.

In 1968 Down Beat magazine announced the break up of Maynard’s big band in an article entitled, “Maynard Ferguson Gets Away From It All – Breaks Up Band.”

He felt from a business standpoint, it was no longer a sensible proposition and he wanted to do something new. The big band scene was at its lowest ebb during the sixties and Maynard felt he was just doing the same things over and over.

So Maynard had realized his wish to front the most swinging ensemble around, one that had captured the delight of the jazz audience. It had experimented with the entire dynamic range, brought forth fresh, imaginative, exciting charts, and allowed the top improvisers of the fifties and sixties to freely express themselves. He continued to play with his sextet, but the Timothy Leary years expanded his consciousness and he and Flo had set their sights on moving to India.

Leaving America – India and the English Years

In 1967 Maynard was offered a gig to front an all–star Anglo-American jazz orchestra (including Clark Terry) on a tour of England. He accepted and took his family with him. The plan was to take them to India at the end of the tour.

The original contract called for three and one-half weeks in Europe, but turned into six years and a new chapter in Maynard’s life. It was at this time that he met Ernie Garside who became his manager. There were several trips to India and the English music world was overjoyed to have Maynard Ferguson living there. He was re-energized by the European music scene and influenced by the music of India with all its expanded time signatures and unique instruments as well as a spiritual path of oneness.

For a while money was tight, so Maynard left Flo and the kids living near the beach in Barcelona, while he and Ernie Garside put the first tour together. It wasn’t long before he had his family on a bus, with a new band, to Sweden and Denmark.

Keith Mansfield came up as a representative of CBS London and couldn’t believe Maynard was in England and not under contract with a record label. Suddenly Maynard was playing all over Europe and loving it. “Maria” (from West Side Story) was a big hit from one of his American albums and so a lot of variety television shows were booking him. They would say, “Oh, we would love to have Maynard on the show to play “Maria.” It was a beautiful arrangement. Maynard’s band even played a weekly spot on the popular English TV program, The Simon Dee Show.

In November, 1968, Maynard and Ernie Garside had a meeting with Keith Mansfield at CBS. CBS had just negotiated a contract with Maynard and wanted Mansfield to be the producer. The label was mostly pop and rock, but the head of A&R and the Managing Director both shared a love for big bands and jazz. That was important, because at that time there was little interest in this area of music from any other record company.

KEITH MANSFIELD

“At a meeting between Maynard, Ernie Garside and the CBS reps, it was decided to record an album of ‘contemporary standards’ (recent show songs and film themes, etc.), featuring Maynard with a large orchestra. This was recorded between the fourth and sixth of December, 1968 at Olympic Studios in London which, although they had the room to record large orchestras, was better known as a rock and roll studio. In fact, much of the Rolling Stones early recording work was done there. It was at these sessions that I first encountered one of Maynard’s unusual ways of dealing with ‘studio stress.’

“I needed to discuss some musical point with him and I walked to his solo booth, to be confronted by his feet where his head should have been. Maynard was literally standing on his head! He would do this for several minutes at a time, often between takes. Yoga was very much a part of his life, and this was one of his ways of dealing with pressure. Once this project was finished, we had to decide in which direction to go next. We discussed the idea of taking the band into areas of music that would appeal to a much younger audience than the ‘straight ahead’ arrangements, which were the staple diet for big band fans.

“One obvious solution was to take the current songs that had enough musical ingredients that would allow an arranger to reinterpret them for Maynard. Another was to write new compositions using ‘rock’ rhythms under good exciting brass writing, with plenty of space for solos from some of the great jazz players that Maynard always seemed to attract into his bands. A fine example of this was ‘Give It One’ which Alan Downey arranged and co-wrote with Maynard.

“Anyway, CBS agreed to let us go in this direction, and so began the ‘MF Horn’ era.”

While Maynard continued to enjoy life in England and tour Europe with his British band, the MF Horn albums and the Alive And Well In London album were building a new audience back in the United States.

In 1971 Maynard began his first tour of the U.S. with his British band. The concert was New York’s Town Hall and the applause was near to riotous. There were many tours to follow and Maynard’s decision to incorporate contemporary music into his book turned on a whole new generation.

DOWN BEAT MAGAZINE – April, 1972

M.F.’S BACK IN TOWN

“Maynard Ferguson has been gone from the United States for four-and-a-half years, living in England and for a time in India. He left this country in a darkness – an interlude of artistic withdrawal and private despair, facing financial ruin; he broke for a new life and found it on the other side of the ocean. And now he was back, on his second U.S. tour in two-and-a-half months, his sound, his soul on fire with today.

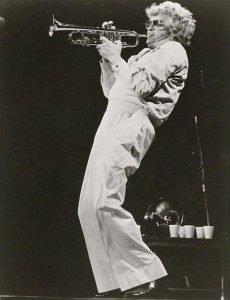

“The place: the dressing room of Brandi’s Wharf, a pleasant supper club in Philadelphia. The scene is surreal: Maynard on a meteoric warm-up streak, hitting a high note, whirling in slow motion; fans, people running in and out; Maynard moving into his strange Hatha Yoga breathing exercises, stretching, leaning, his entire body seeming to fill with air. Then he’s resting a moment, taking a sip of coffee, posing for a photograph, somehow alone in the madness, a boyish shyness showing through it all.

“His band explodes in pockets of energy around him – young, bursting, funny, colorful – a rebellious bunch of crazy English characters who also happen to be talented, serious musicians.

“You know,” he says softly, “an instrumental player is a mystic communicating with sounds, not language. Instrumentalists have many experiences. It’s hard for them not to have magic involved in a performance.”

“The audience, riveted, watches him moving, feeling it through his horn, telling it all – his pathos, his ecstasy. An audience consumed, gone with him. Later, alone, he gathers his energies, free inside. After a while, he speaks, his voice strangely suffused. “You know,” he says, “after I play like that I really feel happy.”

Maynard’s travels had taken him to England and India. His work outside the United Kingdom included sojourns through Western Europe, the Scandinavian countries, and parts of Eastern Europe. His new band with its contemporary charts was a hit and Maynard was ready to move back to America. He and Flo were happy to return with their family to sunny California.

Return to America

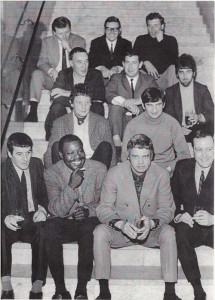

With Maynard’s return to the States the Willard Alexander Agency booked the band at jazz clubs, festivals, universities and high schools across the country. His new young fans were a powerful and charged audience.

Maynard and his band had the time of their lives living on a cramped road bus traveling back and forth across the country. Every gig was fun, but there were spots in the country that were extra special. Places where the kids went nuts. They were Maynard Fanatics. The Great American Music Hall in San Francisco was always packed with parents, band directors, music students and screaming kids. All excited about jazz. These were some of Maynard’s favorite gigs to play.

No matter the energy he used on stage, Maynard had plenty left to talk with kids and parents after the shows. He thrived on the interaction and developed a huge fan base that he knew by sight and often by name. Some nights the bus would be loaded and the band would wait an hour for Maynard to finish signing autographs, swapping stories with the local band director or giving a young student an impromptu trumpet lesson.

MARK ALDERMAN (Fan and Friend)

“The year was around 1974. I was a trumpet major at West Virginia Tech in Montgomery, West Virginia. At that time Maynard was playing with a full big band. I arrived at the Tech Ballroom three hours before the band’s arrival just so I could sit right in front of Maynard. I wanted to watch him breathe and approach the trumpet. I heard him in the back warming up and then he came out for a mic check and blew me away.

“Maynard saw my big smile and stepped off the stage and said “What’s your name son?” I said, “Mark Alderman Mr. Ferguson.” He said, “Call me Maynard,” and shook my hand. I was awestruck. He asked if I played trumpet and I said, “I sure do.” He then asked which tune I liked the best and I said, “Give It One”. He said, “Mark get out your trumpet and warm up with us.” So I did.

“I was getting a little nervous. Then Maynard looked at the band and said “Welcome Mark Alderman, he is going to play ‘Give It One’ with us.” So reluctantly I walked back into the trumpet section and stood between Lynn Nicholson and Stan Mark. Before I could comprehend what was happening Maynard counted off, “1!, 2!, 1! 2! 3! 4!”

“He even let me scream some of the lead licks. What a thrill for a young kid. After the concert I ran over to the dorm to get my MF Horn IV and V album. Maynard had already gotten on the band bus to relax – he had a beer in a plastic cup – and I said, “Boss would you sign my album set?” Maynard said “Sure! Hold my beer.”

Roaring through the 70’s

In 1974 Maynard brought his new band into the studio in New York to record the Chameleon album for CBS/Columbia. The band personnel were now half English and half American and Maynard played trumpet, baritone sax, superbone (an instrument he designed) and sang. The album sold very well and included the tracks: “Chameleon,” “Gospel John,” “The Way We Were,” “La Fiesta,” “Jet,” “I Can’t Get Started,” “Living For The City” and “Superbone Meets the Bad Man.”

He licensed his more popular charts like “Gospel John” and “Chameleon” to various print publishers for release as stage and marching band charts. With each new album release always came a couple of new charts.

JOE MOSELLO

“In the 70’s it was the peak period of the stage band renaissance in the schools. I felt like one of the Beatles when we’d get to those schools. Every time you’d pull up to a gig, all the trumpet players would mob you and all the band kids would come around and be so excited. You felt like a movie star! They’d ask you about your horn, your equipment and even want your autograph. It was a thrilling time for me.”

ALAN ZAVOD

“It was 1974. I was teaching at the Berklee College of Music in Boston when I was asked to sub for Maynard’s keyboard player who was on his way from England to join the band. It was to be a week of rehearsals and three gigs. Three days and I was in love. Maynard brought out the animal in all of us. This was too much fun and during that week I threw Maynard my best boyish grins in the hope that he would keep me on. A week turned into a year.”

In 1975 the band, augmented by many studio musicians, recorded the album Primal Scream. For this recording Columbia was trying new producers and asked Maynard to work with Bob James. Primal Scream was the first collaboration album Columbia intended for the new burgeoning fusion audience. While Maynard was frustrated by lack of control and choice of musicians, he decided to be open and give it a try. “Pagliacci,” the powerful live performance piece that Maynard’s touring band had developed, was part of the recording. The crossover success of the album would send Maynard back into the studio with Bob James for the next album.

One of Maynard’s proudest moments came when he was asked to perform at the closing ceremonies of the 1976 Montreal Olympics. They had him way up in the air on a small pedestal with no railing. 350 girls in French costumes were doing their big dance number far below, when suddenly a man ripped off his clothes and started running naked on worldwide television. It was not long after Munich, so there was a lot of security.

MAYNARD

“Suddenly, from out of nowhere, a guy in a SWAT team uniform (with everything from grenades to high powered guns) drops onto the podium. The funny thing was he said to me, ‘Freeze, stay where you are!’ Now where the hell was I going to go? I was hundreds of feet in the air. They would have shot him, I think, except there were all these girls dancing around him, laughing. So anyway, I blew out the Olympic flame and my whole family was there watching. There were 75,000 in the audience and two billion watching around the world.“

In 1977 Maynard was invited to record with an all-star cast in Montreux, Switzerland for a live recording of the Montreux Summit. The performance yielded two double-LP albums released in 1977 and 1978. The all-star contemporary jam session was a memorable reunion for Maynard. Woody Shaw, Slide Hampton, Hubert Laws, Stan Getz, Benny Golson, Dexter Gordon, George Duke and Freddy Hubbard were just a few of the performers involved.

Maynard’s career was on a high. In order to outdo the 1975 recording of Primal Scream, forty-seven musicians were used to lay the tracks on a monumental album recorded in New York and San Francisco, Conquistador. Maynard played trumpet, superbone, firebird (another instrument he designed which was a Combination valve and slide trumpet) and flugelhorn, and it was an international hit. In 1977 the track “Gonna Fly Now,” was released as a single and invaded the billboard pop charts. Band kids everywhere were running to band class and trying to play like Maynard.

Leonard Feather – The Los Angeles Times

“The recording of ‘Gonna Fly Now’ from Rocky catapulted Maynard Ferguson into “Pop” popularity with a top 10 single, a gold album, and one of his three Grammy nominations in 1978. Maynard accomplished what no other jazz artist had. Conquistador earned Ferguson a unique place in the big band world; he alone was able to crack the pop charts.”

Maynard was grateful to Columbia, especially during the initial years when Bruce Lundvall was president. He went on to record: New Vintage (1977), Carnival (1978), Hot (1979), It’s My Time (1980) and Hollywood (1981). Maynard’s last Columbia Records album, Hollywood, earned a Grammy nomination as Best Rock Instrumental for the track “Don’t Stop till You Get Enough.”

Unfortunately, Maynard’s long tenure with his label had begun to sour. Bruce Lundvall was no longer president and Maynard didn’t have artistic control. The new execs at Columbia, who knew little about Maynard’s tremendous live audience, were trying too hard for another hit, and were barely interested in promoting the real Maynard Ferguson. Though producers chose A-list studio musicians, Maynard felt that his guys had been playing the charts night after night on the road and should be playing on the records.

MAYNARD

“It was obvious to me we were no longer in sync like a team. When the time came to renew my contract I never went there to sign and gave up the big advance. The End.”

Independence,

High Voltage & The Big Bop Nouveau Band

In the 1980’s Maynard Ferguson moved to independent labels where he was free to explore new ideas and produce many of his own albums. Of note, Live From San Francisco was the first live album since Live at Jimmy’s in the early 70’s and captured the passion and excitement that couldn’t be recreated in the studio.

Maynard’s bands were still touring the world extensively, and the biggest MF fans were the musicians who shared the stage with him. Beyond his extraordinary ability as a musician and the mind-boggling high notes, was his capacity as a mentor and band leader. He respected his musicians, and showcased their talents at every concert.

Bob Militello describes his first gig with Maynard.

BOB MILITELLO

“Maynard has a way of finding out what you have to offer quickly. Mike Migliore had recommended me to Maynard and had told him I was a great sax player, but that I did some really different stuff on flute. At the time we had a chart by Jay Chattaway called ‘Foxfire.’ Maynard asked me to play a solo on flute in this number. Well, didn’t know that Migliore had told Maynard about my flute playing, so I went up to the mike and started playing my solo. After a couple minutes, Maynard cut the band out and had me continue playing by myself. When I looked over after a couple of minutes, Maynard was standing on the side of the stage and obviously wanted me to keep playing. Well, after I finally finished my solo, I got a standing ovation from the audience and now had a major solo every night. This was Maynard’s way of drawing out whatever you had to offer, making it clear to you that he had no problem sharing the limelight and giving you a forum in which to exploit your potential as a player. Throughout my stay on the band I saw him do this with everyone who came on the band.”

True to his mantra of change, Maynard’s band was constantly evolving. When Maynard wanted to play in a smaller group, the High Voltage Band was born. It was an experiment with electronic music that resulted in the albums High Voltage and High Voltage 2. Maynard enjoyed the experience and felt that he learned to be a better producer, but soon had the urge to play with other horns again.

By the late 80’s Maynard returned more to his roots of traditional jazz when he formed the Big Bop Nouveau Band. The band’s repertoire included original jazz compositions and modern arrangements of jazz standards, with occasional pieces from his 70’s book and even modified charts from the Birdland Dream Band era.

MAYNARD

“But it never felt to me as though I was going back to something old by getting a big band together again. It felt as though I was going forward into something new.”

An Emphasis On Education

The focus on music education that Maynard began in the 70’s was contributing greatly to the future of jazz. With his 200+ performances per year, he offered clinics at all high school, university, and conservatory appearances. There were now decades of young musicians infected with Maynard’s positive approach towards music.

DOC SEVERINSEN

“I always thought when Maynard was out on the road with his band, what a great thing he was doing. He gave up the comfort of playing the studios where he could have been home and probably done very well financially. He was out there with that big band keeping jazz going and keeping big bands going at a time when no one else was doing it.”

The band was often contracted to arrive in the afternoon for Maynard to perform one of his charts with the school marching band at the football halftime, or to give a clinic. In the evening, there would be a concert in the auditorium or gymnasium. The acoustics may have been awful, but who could tell with thousands of excited screaming kids packed to the ceilings.

At the end of the performance, Maynard would bring the entire school band, or just the horns, on stage to perform the big “ta-da” closer of the tour. It was “Hey Jude” in the early 70’s, and later became the theme from “Pagliacci.” Towards the late 70’s, the theme from “Rocky” took its throne as the closer and the decibels from the audience were earsplitting.

THE WASHINGTON POST

“Ferguson lit up thousands of young horn players, most of them boys, with pride and excitement. In a world often divided between jocks and band nerds, Ferguson crossed over, because he approached his music almost as an athletic event. On stage, he strained, sweated, heaved and roared. He nailed the upper registers like Shaq nailing a dunk or Lawrence Taylor nailing a running back — and the audience reaction was exactly the same: the guttural shout, the leap to their feet, the fists in the air. We cheered Maynard as a gladiator, a combat soldier, a prize fighter, a circus strongman — choose your masculine archetype.”

Maynard Ferguson created the kind of life all artists hope for. He traveled the world with musicians he respected, playing the music he loved.

He performed with iconic jazz legends and band kids just starting out, jammed with kings and presidents and was honored with countless awards. He played in the bands of his childhood idols and became a bit of an idol himself. His “never look back” and continual refreshingly optimistic approach to everything in life, won him admiring fans throughout the world.

Will there ever be another Maynard Ferguson? Each night before he would enter the stage he would silently appreciate his talent with the hope that he would not disappoint his audience, the musicians and listeners who have warmly appreciated him over the decades. Disappoint us, Maynard? NOT A CHANCE.

MAYNARD FERGUSON

“Music is a great source of pleasure; the enjoyment begins with your very first notes. . . and it should never stop. And remember, there is no prophet you can go to for all the answers. The only real prophet is the one that sits in a lotus position inside your own brain, your greatest teacher and critic is right there.”

*This collection of stories is a small peek into the life of Maynard Ferguson. His career spanned so many decades and music genres that even a glimpse takes more than ten pages. Mostly taken from the book MF Horn written by Bill Lee and edited together by Wilder Ferguson-Jacob

——————–

Maynard Ferguson’s musicians have encompassed the “Who’s Who” among musicians in the second half of the twentieth century. A greatly modified list would include

Arrangers-Composers; Mike Abene, Manny Albam, Bob Brookmeyer, Jaki Byard, Al Cohn, Chick Corea, Denis DiBlasio, Tom Garling, Herb Geller, Slide Hampton, Bill Holman, Bob James, Willie Maiden, Johnny Mandel, Chip McNeill, Marty Paich, Don Rader, Shorty Rogers, Ernie Wilkins;

Vocalists: Patti Austin, Kay Brown, Chris Conner, Irene Kral, Annie Marie Moss, Matt Wallace;

Saxophonists: Pepper Adams, Al Cohn, Mark Colby, Denis DiBlasio, Jimmy Ford, Jimmy Giuffre, Bob Gordon, Carmen Leggio, Joe Maini, Rick Margitza, Charlie Mariano, Chip McNeill, Don Menza, Lanny Morgan, Art Pepper, David Sanborn, Wayne Shorter, Lew Tabackin, Matt Wallace;

Trumpets: Bill Berry, Randy Brecker, Joe Burnett, Conte Candoli, Bill Chase, Buddy Childers, Don Ellis, Rolf Ericson, Bemie Glow, Ray Linn, Stan Mark, Marky Markowitz, Dennis Noday, Al Porcino, Don Rader. Shorty Rogers, Ernie Royal, Bobby Shew, Lew Soloff, Marvin Stamm;

Trombones: Wayne Andre, Milt Bernhart, Eddie Bert, Bobby Brookmeyer, Bob Burgess, Billy Byers, Jimmy Cleveland, Don Doane, Tom Garling, Urbie Green, Slide Hampton, Rob McConnell, Don Sebesky, Bill Watrous;

Guitar: George Benson, Larry Coryell, Eric Gale, Barney Kessel, Steve Khan, Jeff Mirenov, Lee Ritenour;

Veena: Vemu Makunda;

Piano/Keyboards: Mike Abene, Ian Bernard, John Bunch, Jaki Byard, Chick Corea, George Duke, Russ Freeman, Lorraine Geller, Christian Jacob, Bob James, Hank Jones, Roger Kellaway, Bobby Timmons, Claude Williamson, Joe Zawinul;

Bass: Don Bagley, Ray Brown, Red Callendar, Stanley Clarke, Curtis Counce, Richard Davis, Eddie Gomez, Milt Hinton, Red Kelly, Will Lee, Ron McClure, Red Mitchell;

Drums: Larry Bunker, Jimmy Campbell, Peter Erskine, Chuck Flores, Steve Gadd, Jake Hanna, Rufus Jones, Don Lamond, Shelly Manne, Max Roach, Tony Williams.